It's not a good time to be a professional photographer. Ten years ago, digital cameras were bulky novelties that saved your 640×480 pixel image onto a floppy disk. Today, most people can (and do) take better quality photos with their cell-phones.

Meanwhile, at the same time that every man and his dog has a decent quality digital camera and access to cheap tools to touch-up and share their photos, demand for quality is actually going down: the difference between professional and amateur is much less noticeable when compressed for Internet delivery and displayed on an LCD screen at 72dpi.

Sites like iStockPhoto are riding this growing trend, attracting masses of photographers to sell their shots at rates that would be insulting to professionals, but that are flattering to amateurs looking only to make enough to maybe buy a new lens, happy just to know that someone thinks their snap is worth paying for.

News agencies know on what side their bread is buttered. The online version of the Sydney Morning Herald regularly accompanies current-events stories with calls for readers to send in their photos for publication, and they're certainly not rushing to compensate the photographers for the rights.

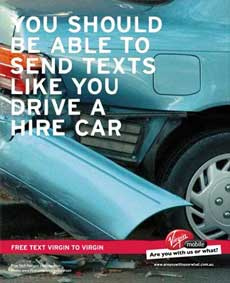

A recent campaign from Virgin Mobile in Australia also skipped the annoying step of having to pay for photography, basing their billboards on appropriately Creative Commons-licensed photos found online.

I noticed these adverts in my local train station1 largely because the not-so-small print included a link back to the Flickr page from which the photograph was obtained. Obviously, this is a logical move on the part of the advertising firm. There's so much free stuff out there, why pay when you don't have to?

Needless to say, there was a certain amount of discussion about this over on Flickr.

Flickr's default copyright setting for new photos is “All Rights Reserved”, so I have little sympathy for anyone who chose to make their photographs available for commercial use, then suffered “sharer's remorse” when someone actually took advantage of that licence.

Similarly, while it can't be fun to be a commercial photographer right now, I can't really condemn any photographer for wanting to share their photographs, or any consumer taking advantage of what is freely available. The number of people who take photos is always going to dwarf the number willing to make the substantial effort to turn that into a business, and the combination of digital photography and the Internet makes it almost easier to share than not.

Technology has radically overturned the balance of supply and demand, flooding the market with an abundance of cheap product which, while a lower quality on average, still contains quite a few gems2. You can't put the genie back in the bottle.

One interesting issue did, however, come out of the discussion of the Virgin billboards. In many jurisdictions, even though it is legal to photograph people without their permission, the rules change when the photograph is used for commercial purposes3. Standard practice is for photographers to get a signed “model release” from anyone appearing in such photos. Very few amateur photographers carry around model releases, even those who later release their photographs under licenses that allow for commercial reproduction.

Version 1.0 of the Creative Commons licence was pretty clear where the responsibility lay. Section 5 (Representations, Warranties and Disclaimer) read in part:

By offering the Work for public release under this License, Licensor represents and warrants that, to the best of Licensor's knowledge after reasonable inquiry: Licensor has secured all rights in the Work necessary to grant the license rights hereunder and to permit the lawful exercise of the rights granted hereunder without You having any obligation to pay any royalties, compulsory license fees, residuals or any other payments;

In other words: if you make your work available for commercial use, it's your responsibility to make sure everything in the work has been cleared for that use. Given that the model release is standard practice in photography, nobody could argue that it isn't part of the “reasonable inquiry” expected of a photographer.

This term caused a certain amount of backlash from bloggers worried that it imposed too much of a financial risk on Creative Commons licensors4. As such, this clause is conspicuously absent from version 2.0 of the licence, the version that is applied to Creative Commons photographs by Flickr. Does this absolve the photographer of responsibility? I am not a lawyer, but my guess is that the answer would be the sort of ‘maybe’ that makes lawyers salivate. Removing the clause takes away the voluntary assumption of responsibility, but only replaces it with the sort of catch-all disclaimer that courts look for reasons to ignore.

Unlike sharer's remorse, where a licensor belatedly realises the obvious implication of the licence they chose, this is a legal minefield that an amateur photographer may not even know they're getting into, and that could expose them to quite substantial liability. Perhaps the commercially friendly Creative Commons licences need to come with a warning label?

Update: I had a chance to talk about this with a Real Lawyer who works for the Australian Copyright Agency. According to her, Virgin would only be in trouble for including people in photos if they were implying some kind of endorsement of their product from the person pictured (which isn't likely), or if the person pictured was under 18 (in one photo, true). So the risk isn't so great after all.

1 The image this billboard was derived from is under a share-alike licence, which I'm assuming makes it OK for me to reproduce it here

2 Of the nine random photos on my last visit to Flickr's interesting photos page, two were Creative Commons-licensed, with one of those free for commercial use.

3 To further confuse things, “commercial use” has several meanings. The Creative Commons defines commercial use as you'd expect: exchanging copyrighted works for money. The New South Wales law regarding the use of your likeness in photographs, on the other hand, defines it much more narrowly.

4 I vaguely remember Dave Winer writing something about it, but can't find the link